TW: Abortion

I had an abortion when I was 17. It was not dramatic or tragic. It was safe, legal, and entirely uneventful; a straightforward medical decision made because of the simple fact that I did not want to be a mother. And that’s precisely why it matters politically. Because it’s not only the sensationalised ‘extreme cases’ that are under threat, it’s the ordinary ones. The quiet, common, deeply personal decisions that become political targets when the far right begins to gain ground.

In the United States, we know all too well what happens when such decisions become entangled in religion and begin to be re-framed as public controversies rather than private human rights. The Supreme Court’s 2022 decision to overturn Roe v. Wade did not begin with total bans; it began with incremental restrictions such as shortened time limits, mandatory waiting periods, targeted clinic regulations. The strategy was to make abortion appear rare, morally questionable, and always exceptional. Over time, ordinary, uneventful, yet profoundly vital abortions like mine were pushed out of reach for millions of Americans.

Reform UK, under Nigel Farage’s growing influence, appears to be adopting a similar rhetorical strategy.

In November 2024, Farage publicly questioned the 24-week abortion limit, suggesting it was inconsistent with advances in neonatal care and ‘worthy of debate.’ While he claimed to be pro-choice, the implication was clear: that some abortions, perhaps most, ought to be reconsidered by Parliament. This is not a medical argument, it’s a political one. And its logic mirrors the American far-right playbook: raise doubts, provoke division, and open the door to legal rollback.

We cannot afford to treat these statements as neutral. When populist parties begin to question reproductive rights, particularly under the guise of ‘common sense’ or scientific concern, it is often the beginning of a broader campaign to delegitimise bodily autonomy. We have seen it in Poland, where the far right has driven one of the most extreme abortion bans in Europe. We have seen it in Hungary, where conservative family policy is now a tool of demographic engineering. And we are now seeing the early signals in Britain.

My abortion was unremarkable. No lasting emotional impact, no medical complications, and certainly no regret. That is its political significance. It was one of thousands that happen every year, with little drama and immense personal clarity. But under a far-right populist government, or even a Parliament reshaped by Reform UK’s influence, such experiences may no longer be accessible, let alone acceptable. That is the future we must fight to prevent.

The rapid rise of Reform UK, a far-right populist party now leading in national polls, marks a worrying shift in Britain’s political terrain; one that threatens to roll back hard-won women’s reproductive rights. While the party’s official platforms remain vague on reproductive issues, its alignment with nationalist, anti-‘woke’ rhetoric and traditionalist values raises serious concerns about the future of bodily autonomy in Britain.

Let’s explore how Reform UK’s ideology and growing influence could reshape the politics of reproductive rights, placing the UK at a dangerous crossroads between progress and reaction.

Reform UK began as the Brexit Party in 2019, a vehicle for Nigel Farage to push for the UK’s departure from the European Union. Once Brexit concluded, the party rebranded in early 2021, shifting from a narrow Eurosceptic (opposed to increasing the powers of the European Union) focus to a broader right-wing populist agenda. Its platform now centres on a commitment to shrinking the size of government and reducing taxes, proposed reforms to the NHS, and, most blatantly, strict immigration control and aggressive opposition to what it labels ‘woke’ culture. It’s worth noting that one in seven Britons (15%) define ‘woke culture’ as the ‘awareness of political and social issues’.

The party’s leadership is spearheaded by the notorious Nigel Farage, a veteran figure on the populist right whose previous roles with UKIP and the Brexit Party have made him synonymous with Britain’s anti-establishment politics. Alongside him is Richard Tice, a businessman and long-time Brexit advocate who currently leads Reform UK and plays a key role in shaping its economic nationalism and anti-elite rhetoric.

By framing abortion law as a subject for parliamentary re-examination, Farage opens the door to potential rollbacks of reproductive rights, mirroring the rhetorical strategy of far-right populist parties elsewhere. His remarks suggest that Reform UK, while not explicitly campaigning on abortion, may be sympathetic to policies that restrict reproductive autonomy under the guise of scientific or moral reconsideration.

His 2024 statement, thankfully, was quickly challenged by cross-party MPs, health professionals, and reproductive justice advocates. Labour MP Stella Creasy responded: “Ninety percent of abortions happen in this country before 10 weeks – those rare ones that do happen later are the most heartbreaking as they often involve fatal conditions that mean much longed-for children do not survive birth.”

Remembering this is imperative to the reproductive rights debate, especially when prominent political figures such as Donald Trump fuel the fire of reproductive misinformation. In a recent debate against the former president, Joe Biden, Trump stated that Biden’s position on restoring abortion access would lead to doctors being able to ‘take the life of the baby in the ninth month, and even after birth’. Not only is this a wildly dangerous rhetoric to be attempting to convince the public of, it’s simply just profoundly incorrect. Chief Medical Officer of US based Partners in Abortion Care, Dr. Diane Horvath, reasoned that in all the time she’s been practicing abortion care, she’s never seen a patient who walked in during their third trimester of pregnancy who wanted to terminate simply because they were tired of being pregnant, as some anti-abortion groups might suggest. The idea that people are choosing that path ‘carelessly’ is just wrong.

In England, Wales, and Scotland, abortion is legal up to 24 weeks under the 1967 Abortion Act, requiring approval from two doctors who agree the pregnancy poses greater risk to the woman’s health than termination (this in itself is widely viewed as outdated and in dire need of reform - with more than six in ten Britons (63%) in support of allowing abortions to be approved by a nurse or another medical practitioner, rather than the two doctors needed). Abortions after 24 weeks are permitted only in cases of serious risk to the woman or fetus. Northern Ireland decriminalised abortion in 2019, but access remains limited due to few services and logistical barriers. Public support for abortion rights is strong, with a 2023 YouGov poll showing 87% of Britons in favour. However, challenges persist, including long waiting times for contraceptive services, sometimes up to several months, and funding cuts that limit access to contraception. These issues underscore ongoing barriers to reproductive healthcare despite legal protections.

We saw a major win recently on the 17th June 2025, when MPs overwhelmingly (379 to 137) backed the New Clause one amendment to the Crime and Policing Bill, which could see an end to the threat of criminal investigation and prosecution of women who choose to terminate their pregnancy. The amendment relates to the Offences Against the Person Act of 1861 (yes, you read that right – eighteen sixty one), and the Infant Life Preservation Act of 1929 (not quite as old, but still pushing a century). Tonia Antoniazzi, the Labour MP who put forward the amendment, stated that the Victorian law was ‘originally passed by an all-male Parliament elected by men alone’ and that ‘it is increasingly used against vulnerable women and girls [and] since 2020 more than 100 women have been criminally investigated’.

Reform UK’s platform, unsurprisingly, lacks any detailed policy on reproductive rights, contraception access, or broader women’s health services. We can safely assume that the omission of any policies addressing women’s health or reproductive rights in Reform UK’s platform is not accidental, but rather indicative of a lack of genuine concern for these issues. The party’s 2024 manifesto (‘Our Contract With You’) offers detailed positions on immigration, tax, and cultural matters, yet remains entirely silent on reproductive healthcare, contraception access, or abortion; areas that are central to women’s autonomy and well-being. This absence, combined with Nigel Farage’s history of downplaying gender equality and promoting traditional gender roles, proves that women’s rights are simply not a priority for the party. The consistent neglect of these critical areas reflects not just an oversight but a broader indifference to the needs and freedoms of over half of the population.

On education and gender, Reform UK has pledged to ban so-called ‘transgender ideology’ in schools, proposing the removal of gender identity content from curricula, restrictions on pronoun use, the enforcement of single-sex facilities, and mandatory parental notification if a child questions their gender. These policies reflect a broader commitment to ‘traditional family values’, which Farage frames in terms of restoring Judeo-Christian social norms (on the campaign trail last year, he claimed ‘Judeo-Christian values’ were at the root of ‘everything’ in Britain), boosting birth rates, and incentivising heterosexual marriage through tax breaks and the removal of the two-child benefit cap. Ironically, he has also previously admitted that he ‘may not necessarily be the best advocate for monogamous heterosexuality or stable marriage, having been divorced twice’.

Although Reform UK does not maintain formal affiliations with far-right religious groups, Farage has appeared at the National Conservatism Conference alongside representatives from ADF International, a conservative Christian legal advocacy group known for opposing abortion and LGBTQ+ rights. So what impact does all of this have on the future of reproductive rights in Britain? We have to focus on the emphasis on ‘traditional family values’. By promoting a vision of society where women are primarily valued as mothers and caregivers, the party contributes to a cultural climate that discourages female autonomy and subtly stigmatises reproductive choice.

Nigel Farage’s repeated remarks urging women to make ‘different life choices’ than men reinforce the idea that motherhood is not only natural but expected – framing other paths, such as career prioritisation or delayed childbirth, as deviations from societal norms. Over time, this narrative can influence public opinion, reduce political appetite for expanding reproductive healthcare, and embolden opposition to abortion or contraception access. Additionally, policies that reward marriage and large families while ignoring or undermining support for single mothers, working women, or reproductive education further entrench systemic barriers. In this way, cultural conservatism, framed as pro-family, can have a slow but significant chilling effect on women’s rights by shaping norms, restricting options, and setting the stage for future legislative regression. We have to focus on the long-term, slow effects of Reform UK’s traditionalist mentality, as its impact on women’s reproductive rights is likely to be gradual but deeply consequential. Recognising these slower shifts is essential; the erosion of rights often begins not with a law, but with an idea.

We must not forget that our rights are not guaranteed indefinitely; they can be reversed. The US offers a stark reminder: nearly 50 years of federally protected abortion rights were dismantled in 2022 with the overturning of Roe v. Wade. This wasn’t an abrupt change, but the result of a calculated, long-term campaign by far-right forces to reshape the judiciary and public discourse. What seemed settled was swiftly undone. Rights, once won, still require active protection, and complacency in the UK could open the door to similar regressions.

The Dobbs v. Jackson decision allowed individual states to ban abortion, triggering near-total bans in over a dozen states. States like Texas became hotspots of restriction, leading over 150,000 people to travel out of state for abortions in 2024. Reminder: abortions will happen regardless; the key difference is whether they are safe, regulated, and accessible.

Populist and far-right governments can, and will, erode reproductive rights through legal, cultural, and institutional means. Let’s not forget that 137 MPs voted against the recent amendment to decriminalise abortion (find out how your MP voted here). Although 38% of the population in Britain follows no religion, religious groups in Britain remain steadfast in their pro-life stance, actively lobbying against abortion rights and supporting protests outside clinics. Though a minority, they are vocal and organised, with the Catholic Herald describing the amendment as a ‘hijack’, and Archbishop John Sherrington of Liverpool stating: “We are deeply alarmed by this decision. Our alarm arises from our compassion for both mothers and unborn babies.”

To note: the use of ‘mother’ and ‘babies’ here is a deliberate choice. Women and people who have abortions aren’t mothers in the traditional sense, and medically, it’s fetuses that are aborted.

This is not just a foreign issue; it’s a warning.

Worldwide, threats to reproductive rights and healthcare access disproportionately impact marginalised groups, including low-income women, women of colour, migrant and asylum-seeking women, and LGBTQ+ people. Low-income women are more likely to experience barriers such as travel costs, delays in accessing services, and patchy provision of abortion or contraception, particularly as NHS services face underfunding and regional inequalities. Women of colour face systemic health disparities, including a significantly higher risk of maternal death. Black women in the UK are nearly four times more likely to die in childbirth than white women, a disparity that reflects racial bias and structural inequality in the health system. Migrant and asylum-seeking women encounter legal and practical barriers to care, including the threat of NHS charging, which deters many from seeking prenatal services due to fear of debt or immigration enforcement. A 2021 report by the LGBT Foundation found that 20% of LGBTQ+ respondents believed that maternity services specifically understood or welcomed LGBTQ+ families. The growing influence of Reform UK threatens to deepen existing inequalities and further marginalise those already facing systemic barriers to accessing reproductive and maternal healthcare.

In response to growing threats to reproductive rights and rising far-right narratives, feminist, legal, and healthcare organisations across Britain have mobilised to defend and expand access to care. Groups like BPAS, Sisters Uncut, and the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) have been at the forefront of campaigns to decriminalise abortion, protect patient privacy, and demand equitable healthcare access. Youth-led and intersectional movements have played a critical role in this resistance, countering far-right and anti-choice rhetoric with inclusive, rights-based advocacy. Activist groups have used social media, direct action, and coalition-building to highlight the lived realities of LGBTQ+ people, people of colour, and migrants in reproductive healthcare. As the political landscape shifts, voter engagement and political education have become vital tools for defending reproductive freedom. Mobilising at the ballot box, especially among younger and marginalised voters, is key to safeguarding rights that remain vulnerable to political backsliding.

The rise of Reform UK demands urgent and sustained attention, not only for their stated policies, but also for the dangerous implications of their silence or ambiguity on core human rights, including reproductive freedom. As history has shown, the erosion of bodily autonomy is often one of the earliest and most enduring tools of authoritarian politics. Reform UK’s refusal to clearly support reproductive rights, combined with its broader hostility toward migrants, LGBTQ+ people, and so-called ‘woke’ values, should be taken as a warning sign.

Now more than ever, journalists, voters, activists, and policymakers must recognise reproductive justice as a cornerstone of democratic society. Defending access to abortion, contraception, and inclusive healthcare is not only a matter of health and dignity, it is a defence of individual liberty and democratic accountability.

Silence is not neutrality; it enables regression. The defence of bodily autonomy must be central to any credible pro-democracy movement in the UK, and we have a responsibility to use our vote to protect it.

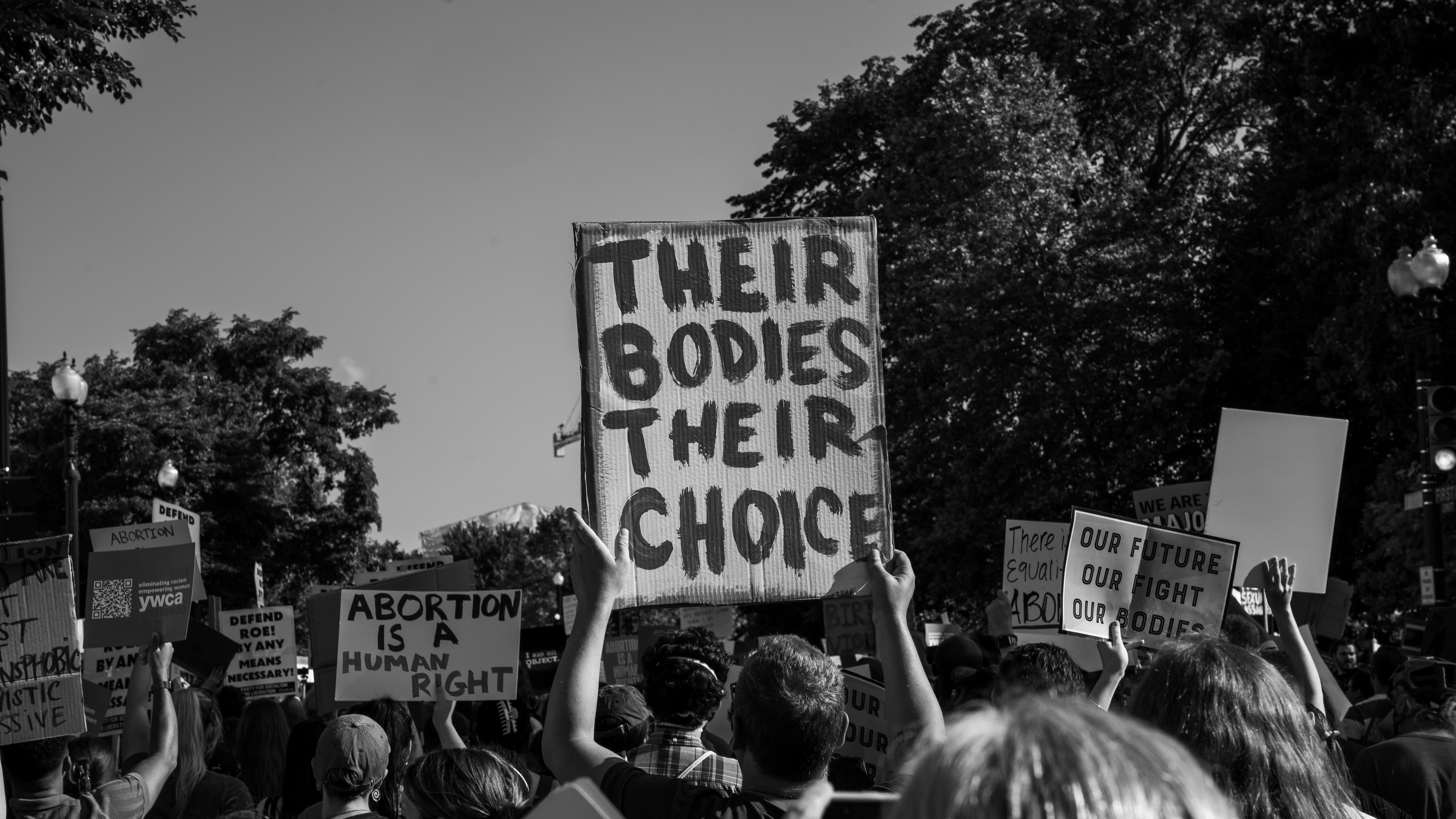

Feature image credit: Gayatri Malhotra on Unsplash