Trigger Warning: This article contains discussion of sexual assault

I avoided watching the Netflix Series, Adolescence, for weeks. I couldn’t really figure out why. The idea filled me with a niggling sense of dread. But I knew eventually, I would have to watch it, so, as I sat, sipping a hot chocolate, my de facto emotional support spaniel next to me on the sofa, the familiar sound of Netflix’s opening chime rang out and it sent a little chill down my spine. At that moment, I was transported back eight years to the cold corridors of my teenage years.

When I was 15, I returned to school after spending four months in a psychiatric hospital following a breakdown. While there, I had disclosed to a therapist the abuse, sexual assault and coercion I had suffered at the hands of a boy in my class when we were both just 13 years old. The abuse had been ongoing for nearly a year. He would show me graphic pornography and explain that this was how I was ‘supposed’ to look, behave and feel. He would force my hand down his trousers, touch me in class and in the corridor, take me to abandoned areas in our neighbourhood and undress himself. All of this was under the guise of what he said was ‘teaching me’. The culture at school was completely centred around the commodification of girls' sexuality, and the dominance, power and sexual prowess of boys. Image sharing came with the growth of social media, and a new language developed from Instagram and Snapchat’s algorithms, which prevented anyone from reaching out to an adult for help or guidance. With little in the way of education or open discussion from either school or parents, I witnessed a generation indoctrinated during the crucial formative years of finding one's identity and embracing sexuality co-opted by violent pornography, a culture of misogyny, body-shaming and hierarchical hegemonic masculinity. \

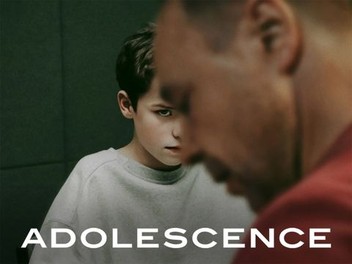

Netflix’s Adolescence has recently crashed into the media landscape, exposing the reality of the dangers of misogyny among young men, as well as the depravity of online influence. These issues are not new, and the post-show mainstream narrative can feel a little disingenuous and dismissive. Shocked headlines flooded in, with calls for showings in Parliament and secondary schools, but what impact will this really have? To what extent can a Netflix drama actually provide the paradigm shift needed to address the culture amongst young people? As sensational and shocking as the show is, it simply shines a light on something that has been happening for years. The show touches on the insidious, complex web of influence in which today's teenagers are entangled: the all-encompassing stronghold of social media on their lives, the scale of disconnect between teenagers and their parents, and the way their formative years are being drowned in relentless tidal waves of exploitative online content. It is indeed horrific – but why are these things such a shock? Watching this cycle of discovery play out again and again is insulting – not only to those who have been fighting to expose reality, but to every survivor who has lived it.

In 2020, Laura Bates published Men Who Hate Women, where she laid bare the growing influence of the ‘manosphere’ alongside Incel communities ‘devoted to violent hatred of women’.The same year, Soma Sara’s book, Everyone's Invited, and its associated charity, created a space where hundreds of thousands of young women shared their stories of abuse and harassment in UK schools. Children as young as years 3 and 4 shared their experiences of abuse by family members, teachers and classmates with overwhelming emotive detail. This is not new.

In episode two of the show, Adam, the son of the lead detective, takes his father aside and explains that the police have been approaching the case the wrong way. Pulling out his phone, he tries to show his father the meaning behind the comments on Instagram: the red pill, the 80/20 rule, and the manosphere.

The detective is painfully ignorant, stuttering about something to do with The Matrix before dismissing the comments as ‘bullying’. The exasperation on Adam’s face is one of the most powerful, relatable representations of the frustration felt by young survivors and allies everywhere.

The fusion of long-standing institutional sexism with the growing, insidious culture of online misogyny has created an impervious barrier between the young people who are living this reality and the adults who have the power to change it. Social media is all-consuming. As we scroll through short, sharp, dopamine hits, the physical world and our perception of our position within it is warped. How does a teenager explain to their parent, who is still suspicious of online banking, the intense feeling of rejection that overwhelms them as their post receives fewer likes than their peers? Online spaces create a cult-like language which separates users from the outside world. These experiences are complicated enough in the relative safety of Facebook jealousy - imagine how isolating it must be for those drawn into the darkest depths of the internet.

Watching the show with my parents, I was struck by their confusion, their desperate attempts to compare this boy’s experience to their own lived experience. But this is different. The language of these influencers poisoning young minds is not one spoken by well-meaning, middle-aged parents. The social media world has the power to consume a young person completely, to close them off from the reality of wider society and enclose them within an endless ecosystem, an echo chamber of increasingly extremist content.

The influence of social media upon young people’s development has rapidly eclipsed that of parents and teachers. The processes of socialisation which help young people to form their identities, self worth and place in the world are no longer solely conducted by the traditional social institutions of schools, families and media. As social media has transformed from a simple app used to message a friend into an omnipresent phenomenon of unbridled power, it has positioned itself as a primary source of influence in the lives of not just young people but society as a whole.

As MPs call for Adolescence to be shown in schools, they are once again missing the mark. The government and media, gushing over the show as though it is a revelation, are playing a desperate game of catch up while young people are already drowning in these toxic spaces. A knee-jerk, performative political response of shoving a deeply nuanced, complex and potentially traumatic television programme into the faces of vulnerable young people will not solve the culture of fear, uncertainty, loneliness and hatred which is consuming young men. Are we really comfortable to rely on a streaming service to educate our children, as opposed to intentional, considered legislative changes?

This malicious culture of misogyny is not just persisting, but actively festering – it is evolving and growing in strength. Andrew Tate has 10.8 million followers on Twitter. This is a man charged, alongside his brother, with sex trafficking, rape, and forming a criminal gang to sexually exploit women, a man who speaks openily about women as subordinate, brainless commodities, with a history of significant violence against them. This is a man who builds an image of masculinity centred on physical strength, dominance, selfishness and sexual prowess, demonising ‘weakness’ in men while offering, for a hefty price, to teach them how to be just as abusive as him.

Tate’s popularity began long after my time at school, but, as I have watched him grow in influence and seen the repercussions play out in the men around me, a deep sense of dread and pain has taken root. Everything he says could have come from the mouths of boys who tormented me at school. He has captured an audience, validating and amplifying the same ideas that were already circulating, making them acceptable and mainstream.

Feminist activists, scholars and advocates have been fighting for centuries to unpick and dismantle the patriarchal structures upon which our society is built. With every win - be it legislative, cultural, political or otherwise - there comes a backlash, a call for a return to the ‘simpler’ times when women remained at home, quiet and in service of their family.

With the inception of social media, and its ability to bridge geographical and temporal boundaries, these murmurs of dissent from the progression of women’s rights are able to take root and gain traction at an unprecedented rate. Where before, these ideas were more commonly associated with the older generation, the internet has allowed these ideas to infiltrate the algorithms of vulnerable young people, planting a seed in the fertile ground of uncertainty and vulnerability which defines their reality.

Young people are facing economic crises, governmental failures, and a future that feels increasingly unstable. They don’t expect to own homes. They have lived through a pandemic. They have seen an irreversible climate disaster unfold. Celebrities and household names are exposed for abuse and corruption almost weekly, stripping them of role models and heroes. They are lost.

Enter: Andrew Tate. Incel groups. The Manosphere.

They capitalise on insecurity. They create a tangible enemy – women. They promise glory, power, and inclusion.

And we are still acting shocked?

What happens when the headlines fade? When it is no longer ‘trendy’ to talk about it?

What happens to the women facing the repercussions of everything discussed in this programme and so, so much more?

Despite the sensationalism of Adolescence, there is an unavoidable and very real physical danger posed by this insidious online culture. In April, two women were seriously injured in an attack by a man with a crossbow in Leeds. The man was later found to have posted a ‘manifesto’ of misogynistic rage to Facebook, and had previously posted about his dislike of ‘gender equality’. This comes less than a year after Kyle Clifford murdered Carol Hunt and her two daughters, Louise and Hannah, with a crossbow. He was later found guilty of rape. Evidence found that Clifford had been watching Andrew Tate’s content in the days leading to his attack.

These are just two examples which happen to have found their way into the mainstream media in the last twelve months. They are not isolated cases.

In the UK, 1 in 12 women are victims of gendered violence every year, and 1 in 4 will be a victim of sexual assault or attempted assault in their lifetime, with even higher figures for trans women and members of the LGBTQIA+ community. It is time to stop viewing these cases in a vacuum and start contextualising them in the cultural reality surrounding us.

Adolescence has provided the world with an opportunity. For all the complexities and controversies the programme evokes, it has opened a crack. We cannot address the epidemic of violence against women and girls without acknowledging and addressing the crisis in mental health experienced by men, alongside the dire lack of regulation of social media. Likewise, we cannot address the mental well-being of men without fully appreciating and talking about the dangers faced and violence experienced by women at the hands of men. We have to accept that these things are fundamentally intertwined. The patriarchal culture which feminism has fought against for so long, and which figures like Tate are fighting to reignite and intensify, is damaging men and women alike. As the mental health, identity and purpose of men is fractured and hijacked by dangerous influence, the physical safety and rights of women are torn to the ground with it. If we genuinely want to see change happen, we must use this opportunity to listen to those organisations who are dedicated to this cause (see RapeCrisis UK, Women’s Aid, Samaritans or find support here). We must, finally, give them the recognition, respect and FUNDING they deserve, and ensure that those in government with the power to regulate – and prosecute – the platforms facilitating this toxicity are held to account.

We must not let the media storm silence the voices of those who are living this reality, or accept performative reform in place of considered, effective change.

As society stands on the precipice of a new technological age, we must take heed of the warnings that social media has shown us. We need to hold politicians to account, to demand that the government step up to protect our young people. Rather than allowing those who lead our country to bend the knee to billionaire tech bosses in some false worship of ‘economic growth’ and ‘technological development’, we should be calling for safe and considered regulation which puts the safety and wellbeing of our community at the forefront. We must fight for schools and educators - those institutions which play a vital role in the upbringing of our children - to have the resources, space and support needed to tackle the complexities of the contemporary world, to be able to teach our young people to think critically and empathetically and have the skills to navigate the technologies of tomorrow. We must fund and amplify the voices of organisations that have been working on the front line as the collateral damage destroys lives. We must call out the media which fail to accurately portray the ramifications of misogynistic violence.

Listen to experts, not film stars; to survivors, not twitter warriors.

Make a stand, while you can.